The Winter Solstice is the shortest day of the year and marks the official start of the Northern Hemisphere Winter. This year here in Colorado, the Solstice occurs at 4:03 pm on December 21st. While there’s no denying that it is the shortest day (and longest night) of the year in the Northern Hemisphere (and longest day/shortest night in the Southern and called the Summer Solstice), the significance of it varies in different communities. It has been celebrated for thousands of years by different cultures. It’s probably the reason that we celebrate Christ’s birth in December since that’s when the Roman pagan mid-winter festivals took place. In my field of meteorology/climate science, the winter season is December, January, February (DJF), so winter really starts on December 1st. For most people, January 1st signifies the start of the New Year. (For me, New Years Day also signifies one of the most memorable days of my life – the birth of my first son).

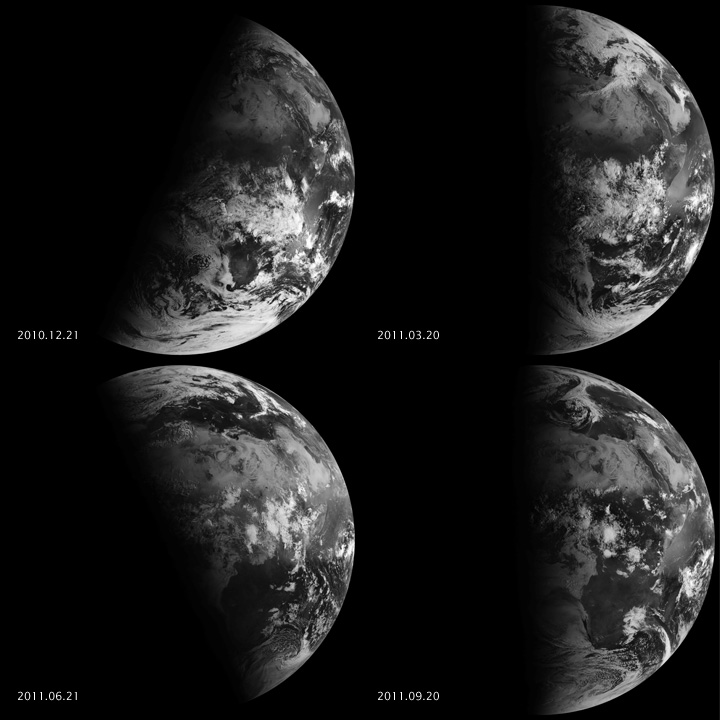

Seasonal shifts of the terminator, aka “Ah-nold”. At the Winter Solstice (upper left), the Northern Hemisphere is tilted away from the sun giving short days and long nights. (Image from NASA)

In beekeeping, the Winter Solstice signifies the start of a new year and the march towards a build up of new bees and rebirth of the hive. In the Fall, the queen stops laying eggs as the cold weather sets in. The Fall-born bees need to live longer than the typical 4-6 weeks, living for several months since no new bees are being born to replace them. The hive population shrinks as the summer bees die off and cold snaps take their toll on the unfortunates on the outside of the cluster. After the Solstice, the days start getting longer and this signals the bees that Spring is just around the corner.

Shortly after the Solstice, the worker bees start raising the temperature in the brood nest to around 95ºF which is required for brood rearing. They use honey for energy and shiver and vibrate their flight muscles to generate heat. The increased heat and the lengthening days signals the queen to start laying eggs. She starts with a small brood patch, and over the course of many weeks expands the size of the nest. By the time the warm weather of Spring rolls around, there will be a large population of bees to take advantage of the new pollen and nectar coming with the Earth’s rebirth.

When I used to teach introductory meteorology classes, I gave the students a set of weather folklore sayings (like “Red sky at morning, sailors take warning”, etc). They would then have to write an essay and explain the science (or lack thereof) behind one of the sayings. (They hated me for this – it was before the days that they could look up the answer on Google). One of them was, “As the day lengthens, the cold strengthens.” While the days are lengthening after the Winter Solstice, we typically get our coldest weather after that date. The nights are still longer than the days, so there is less energy coming in from the sun during the day to warm things up than the Earth is emitting back out to space at night. A similar lag exists in Summer – August is typically the hotter than June (when the Summer Solstice occurs) because of longer days than nights. (That’s your MET101 lesson for the day – there’ll be a test later).

Anyway, back to the bees. An expanding brood nest needs to be kept warm and that requires an ample food supply. Hopefully, the bees have stored enough honey and distributed it evenly around the brood nest so that they can feed on it and “shiver their timbers” to generate heat. The bees are usually balled up in a large cluster with the queen and brood in the center, all trying to keep warm. If there are long stretches of really cold weather, the bees cannot move from the cluster or they will freeze to death. If they can’t break cluster to get to the honey or the cluster isn’t over some honey, they will starve to death. They can literally starve to death within a couple of inches of honey because they won’t move from the warmth of the cluster.

On the other hand, if there is a lot of warm weather, then the bees will be more active. They will fly out of the hive to take their evacuation (“poop”) flights and search for forage. This also uses a lot of energy. Alternating stretches of abnormally warm weather and abnormally cold weather could be deadly to a hive. Sometimes, colonies may go into the winter with too little stored honey – either they didn’t make enough (bad season or too many mouths to feed), or perhaps the beekeeper got a little greedy (most of us aren’t like that, though). Hopefully, the beekeeper assessed this in the Fall and combined weak hives with few stored honey together with hives with more stored honey.

The Solstice is a good opportunity to assess the state of the hive. If it doesn’t have enough food to make it to Spring, the beekeeper can think about supplementing the supply with some honey or sugar fondant. Generally, there will be one or two warm days in the month after the Solstice that will allow the beekeeper to take a peek in the hive (or give it a heft test) to see what stores they have left. Too feed or not to feed is a personal choice – some think it’s artificially propping up a weak strain of bees, others see it as lost money if the hive dies so they feed; there are a variety of reasons for each side. I’m worried about BnB2 since they went into the winter with light stores. I’ll probably make some sugar fondant and put it in the hive soon, just as insurance. I’ll also score the extra combs of honey if they are still full and move them closer to the brood area, so they can more easily get at that. It’s getting harder to get package bees each year and I’d rather requeen if I have to than get all new bees. Last year, I made fondant for BnB1, but they didn’t touch it. They had so few bees, that they didn’t even eat all their honey. I’ll see how they are doing and maybe add some fondant or score the honey. That’s about all I can do at this point! Only time will tell which way the hives will swing after the Solstice!

Okay, now the test question:

Detail the fact or fiction of one of the following weather folklore sayings:

- If bees stay at home rain will soon come; if they fly away, fine will be the day.

- No weather is ill, if the wind is still.

- Ring around the moon, rain real soon.

2 Comments

Julie · December 22, 2014 at 8:32 pm

How are you feeling, Don? Hopefully, you’re back on your feet again.

For starters, I want to say thank you for fueling a long-standing argument between my husband and me. He keeps calling most of Dec autumn because the bounds of winter are marked by the winter solstice toward the end of Dec and the equinox in March. I, on the other hand, define winter as Dec, Jan, and Feb because, despite official dates, those are the cold days!

I’ll also take on your challenge!

If bees stay at home rain will soon come; if they fly away, fine will be the day.

Sure, I’ll agree. My bees stay home if it’s wet or cold. Just like me.

No weather is ill, if the wind is still.

How about the center of a hurricane??? Does that count as disproof? Also, I think we have to define ill. I spent a night in Savannah where there was zero breeze and horrible, oppressive heat. Maybe the weather wasn’t exactly ill, but I was.

Ring around the moon, rain real soon.

I’ve seen lunar halos and coronas but never noticed if they were associated with rain. Coronas are caused by light diffused/diffracted by water molecules, though, right? So, I think this could be true.

How’d I do, Prof?

Don · December 22, 2014 at 11:54 pm

Well, you did so well with the answers to the test, tell your DH I think you’ve earned the right to live by the climate calendar! (DJF, MAM, JJA, SON)

#1 – spot on. Bees generally don’t fly when it’s going to rain!

#2 – Good examples of the outliers! In general, fair weather is associated with high pressure systems and the centers of highs usually feature no or light winds. It’s the subtropical high the gives that “wonderful” weather to Savannah. As for the hurricane – that feature is short lived, but while you are in the middle of it, I’m told the weather is fine. I missed watching the eye of Hurricane Gloria go right over my parents house in CT in 1985 – I left for Maine shortly before it got there, so I didn’t get to test that theory. 🙁

#3 – The halo (ring) around the moon is caused by the refraction of moonlight through high clouds made of ice crystals (cirrus) which can often times be found at the leading edge of a large storm system as it approaches (at least in the mid-latitudes). Through time, as the system gets closer, you should see the clouds become lower and thicker and eventually, you might get some precipitation. See if that happens with your impending Christmas rainstorm (sorry it’s not snow)!

Many times these proverbs are location and season dependent so it’s not always a “one size fits all answer” as you pointed out. But often, they do have a basis in fact! If people tune into their surroundings, it’s amazing what they can observe.

Feeling a bit better – thanks for asking. I made it through a whole day of work today, but I’m glad it’s a short week!